The funeral practices of the Toraja people are unique, as we have seen in the last few blog posts. They have been unique for centuries, though the specific practices have changed over the generations. We visited the Londa Burial Caves, to see an example of how the Torajan people managed their dead some 800 years ago.

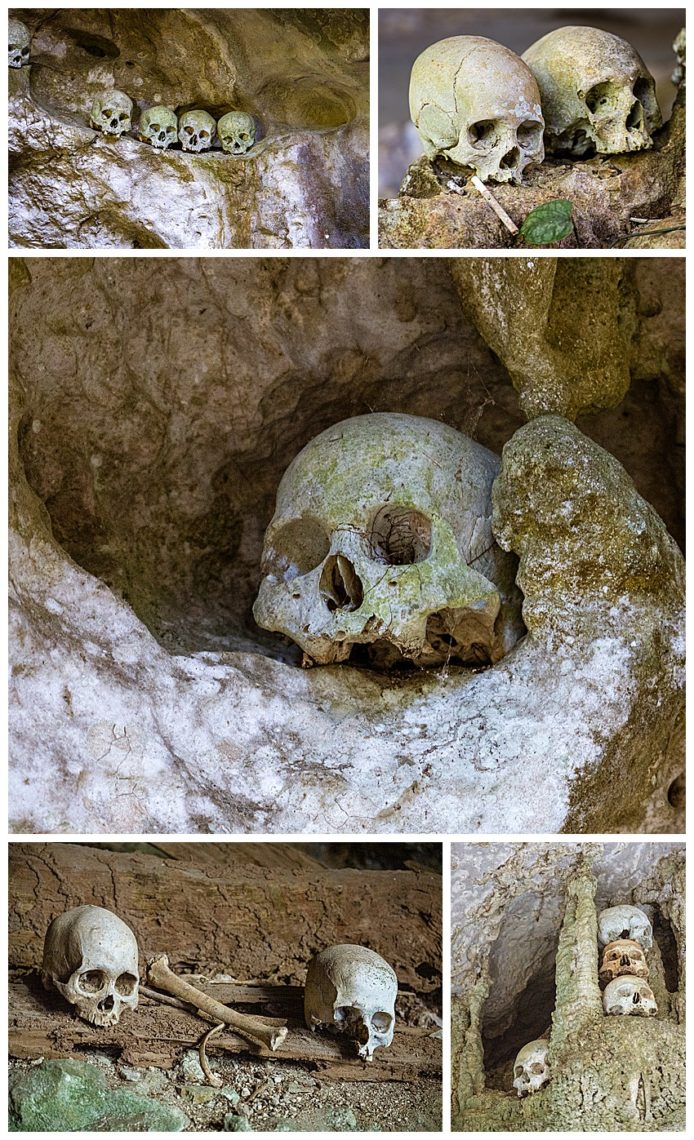

As you enter the burial caves, the first thing you see are rows of human skulls along the floor, and on shelves on the wall. Death is a major celebration for the Torajan people, and plays a significant role in their lives. Contrary to the views of a Westerner, these scenes and celebrations are not at all morbid, as we will see further in upcoming posts.

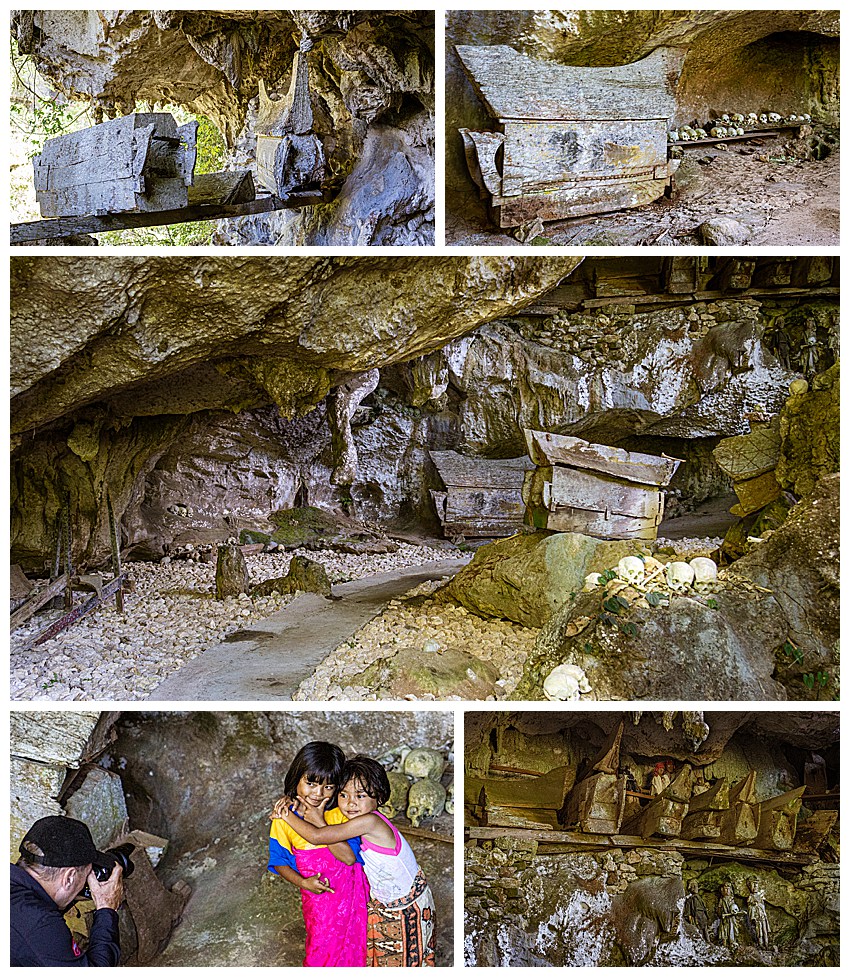

When entering the Londa Cave Cemetery, we felt like we were walking into a scene starring Indiana Jones. There were rows of ancient coffins hung along the cavern walls, with human skulls everywhere. Centuries ago, the bodies of the most prestigious members of the village were buried high in hidden caverns, where thieves would hopefully not bother them.

Torajan people accept death as a normal part of life, and do not fear it. Two young girls follows us into the caves, and obviously considered the coffins and skulls as normal (lower-left).

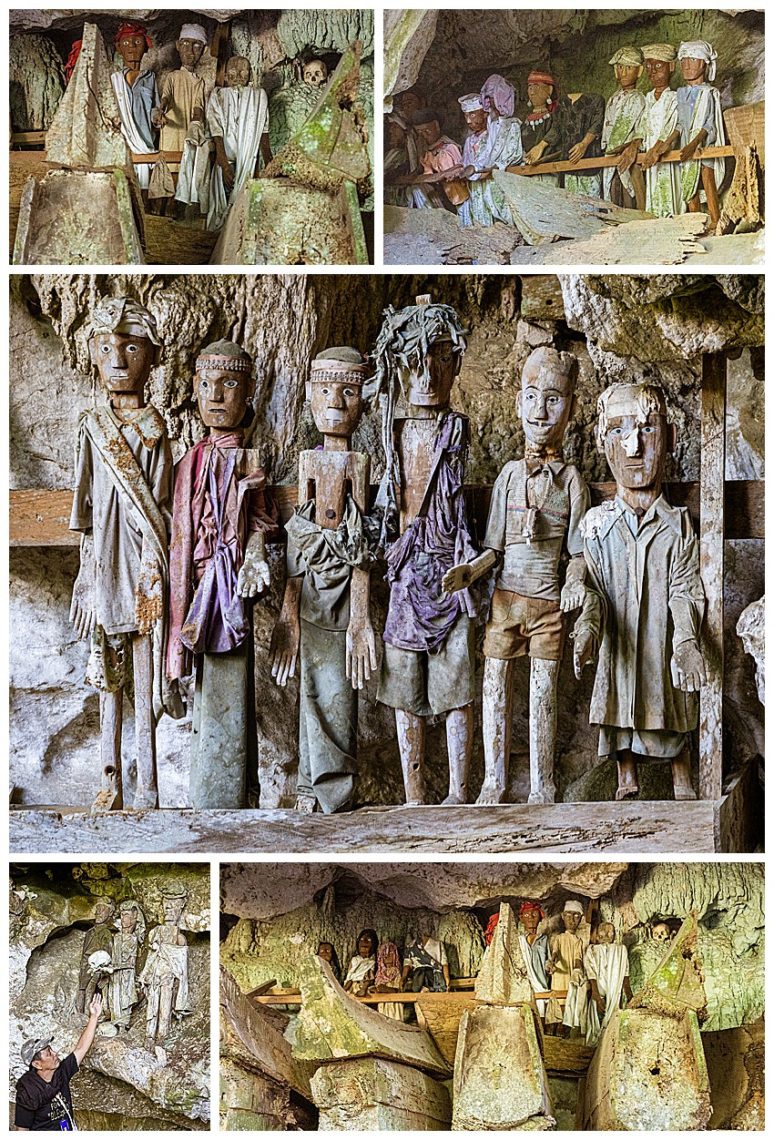

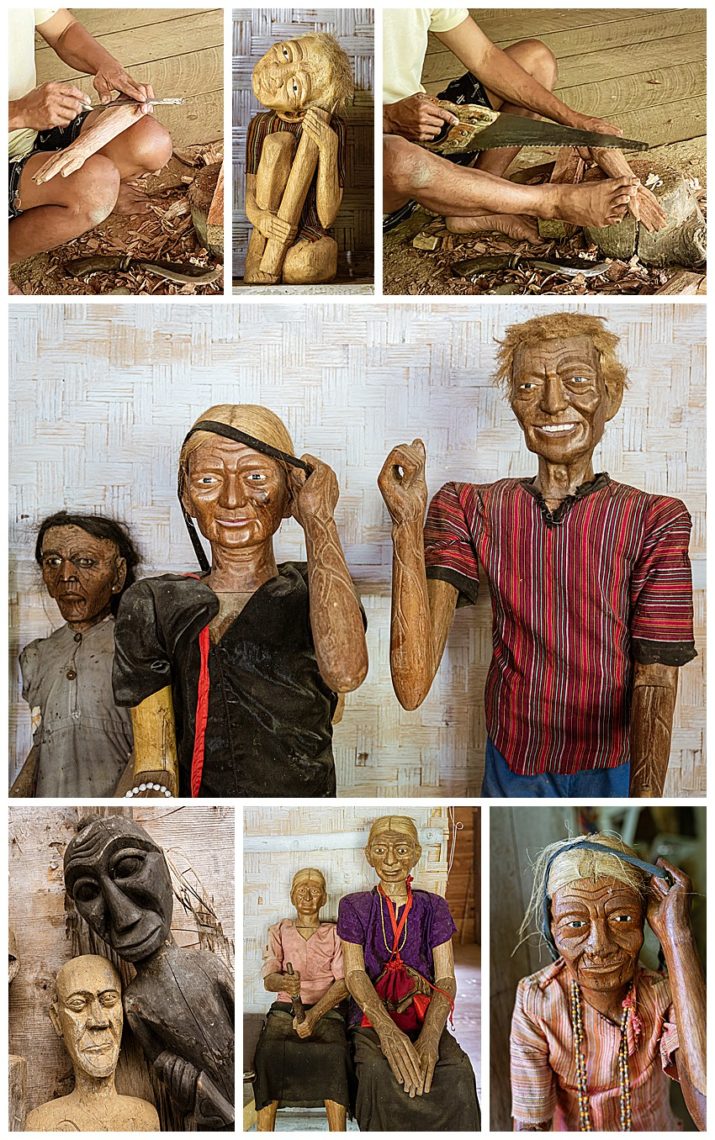

We have seen tau taus (wooden effigies) created for the prestigious village members in the past funerals that we have written about (here and here). These caverns make it clear that there is a long tradition of using them to protect the dead, as they are here, lined up behind the coffins.

Modern tau taus are carved using a photograph as a reference, and look very much like the dead person. Before the advent of photography though, such effigies were more generic, only approximating the visage of the deceased. Our local guide, Sada, shows generic tau taus (lower left), which helps to add scale to the tau taus. Note that they were made to be the full size of the person they represent, but are significantly shorter than a modern person.

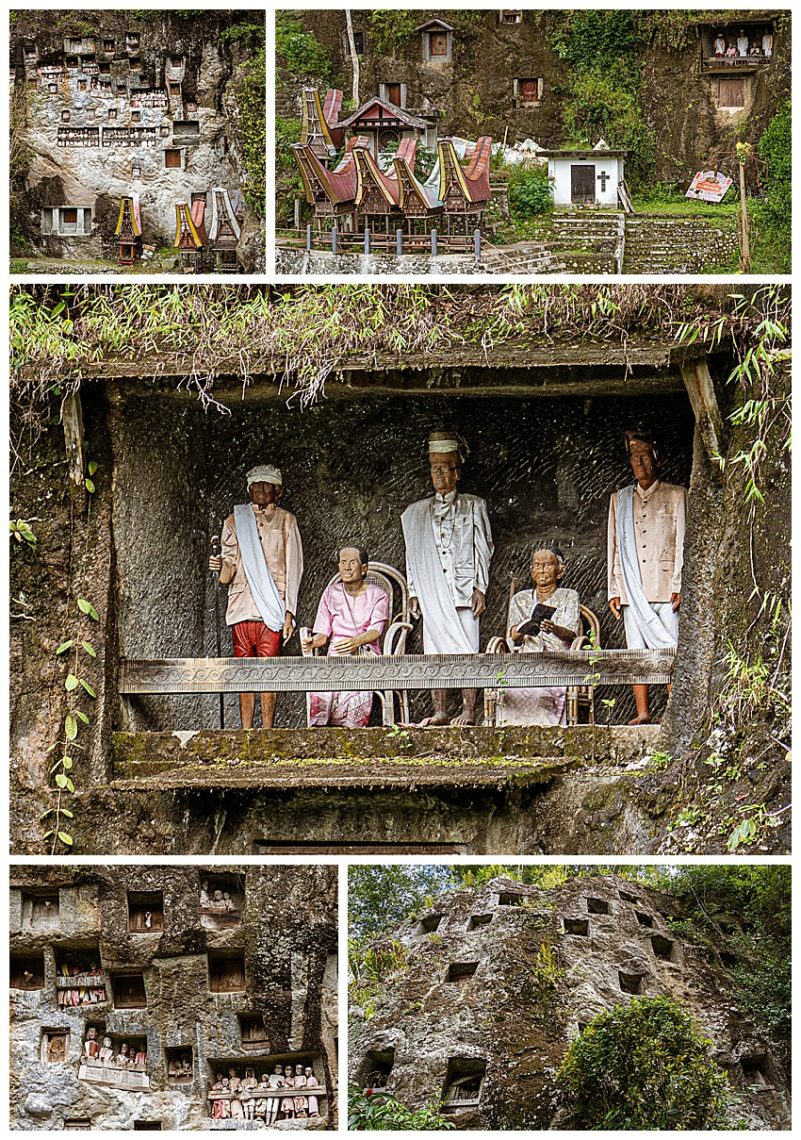

In more recent times, Torajans create their burial sites out of solid rocky cliffs. Slots for the body are carved into the stone by hand, often taking months of laborious work for a single burial (lower-right). Christians in the West often bury their loved ones near their family. Torajans do the same, though they choose a large cliff face in which to carve numerous slots, rather than holes in the ground.

Above is referred to locally as “The Big Stone,” and contains over 100 such burial slots (lower-left). Looking up the face, you can see many with tau taus at the grave entrance (middle-right and top). Many more recent tombs have photographs and frequently replenished offerings, so that the dead is never hungry or thirsty (lower-right). Sometimes dozens of family members, spanning several generations, will be buried in a single slot.

This is a multi-denominational site, and you will see Aluk (the local animalistic religion) buried next to Muslim and Christian. Occasionally, a Christian is buried in a separate house grave (bottom-center), though still near the rest of the village.

Bola bolas are used to carry the body from the funeral celebration to the burial site, and you can see many of them lined up at the base of The Rock. These are from recent burials, and will deteriorate with time, replaced by the bola bola from new burials.

Above is another rock face that has been used for generations to bury the dead, this one in Lemo. This is similar to the Big Stone shown in the prior block. The burial practices we have seen in prior blog posts, and here, are from the beliefs of the Aluk religion, which translates as “The Way,” or sometimes as “The Law.” It is a polytheistic animalistic belief system, in which the spirit of the deceased remains behind until they are properly buried, at which time the spirit proceeds to Puya (heaven). If the body of the dead is not properly handled, and all traditions maintained, then the spirit will remain behind and cause bad luck to the descendants.

Many of the Torajans were converted to Christianity in the early 1900s. The Torajans insisted on continuing their Aluk traditions though, regardless of what the Christian missionaries preached. While it is common worldwide for Christian missionaries to usurp local celebrations and give them a Christian meaning, the Torajans forced the missionaries to their will instead.

Initially, Christian priests refused to attend the Aluk ceremonies that we have been showing in recent blogs, saying that they did not follow the preachings of Jesus. The Torajans ignored the wishes of the priests, and told them that if they did not attend, then they could not have any of the meat from the sacrifices. Since that is the primary source of protein in the local diet, the priests caved. They can now sometimes be seen giving their own blessings, which then results in them receiving a portion of the meat from the animal sacrifices that they disdain.

When we walked around the village of Lemo, we stopped to visit a local tau tau maker. These days, most of the tau taus are targeted to tourists. You can see that the tau tau maker carefully measures (upper-left), then carve the figures using their feet to balance (upper-right). A true tau tau for a prestigious deceased leader of the village may take up to three months to carve.